When Drippy Trees Attract Danger

-

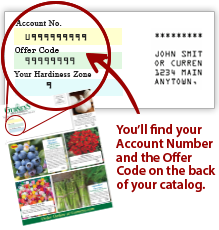

Helpful Products from Gardens Alive!

-

Gardener's Gold™ Premium Compost

Gardener's Gold™ Premium Compost

Q. We recently moved into a home with a lot of trees, including a large oak that wonderfully shades our house and driveway in the summer. However, over the past few days, sap drippings (or something else that is oily but clear) have appeared all over the cars, sidewalk and driveway under the tree; and it's is attracting bees, wasps and hornets. It's becoming a hazard to try and get into our cars or enjoy our front yard. Our five-year-old daughter and many of the neighborhood children play right in front of our house; and she and one other girl were stung by 'bees' over the weekend. Is it normal for trees to drip so much sap that it attracts bees? Do I have to ban my daughter and her friends from the front yard?

--- Steve in Rockville Maryland

A.Wait a minute—haven't I answered this question already in a recent phone call on the show and in a previous Question of the Week? Its aphids up in the tree pooping out their sweet 'honeydew', which in turn attracts all kinds of insects, right?!

Yes and no. Steve might well have aphids in his tree; there's even an aphid species that's specific to oaks. But the wonderful euphemistic 'honeydew' that's pooped out by aphids is blackish in appearance, not the clear material Steve has described. (Aphid honeydew is so dirty looking that it's often described as 'sooty'.) As am I.

Steve's problem sounds more like (and I am not making this name up) 'drippy nut disease'. The unusually warm weather we've had in the mid-Atlantic region this season and the clear color of the fluid are strong clues to this diagnosis. The cause is a bacterium that infests nuts (in this case, acorns) that have been insect damaged, and it won't stop until the acorns drop. So for now, Steve needs to diligently clean the sticky stuff off the driveway and walkway with a pressure washer.

He should also put out lots of wasp and hornet traps to knock down the stinging insect population. And he should collect and destroy all the dropped acorns this fall.

And then there's the cars. He needs to get to a car wash ASAP and get every last bit of that 'sap' off the cars. Then he should try and park someplace else until the acorns fall, use car covers, or rinse the new 'sap' off every day. These drippings can be impossible to remove if left on for a long time.

Now—can this problem be prevented in future seasons?

An important component of trying to prevent future infestations is to avoid using chemical fertilizers on the lawn, or especially on the tree itself. High-powered chemical fertilizers make plants much more prone to insect attack. And whether this is drippy nut disease or oak leaf aphids, insects are at the heart of problem. Use corn gluten meal, compost or a bagged organic lawn fertilizer on the turf and don't worry about getting it too close to the tree; any 'leftovers' will give that oak a nice gentle feeding.

OK—now, let's talk to all trees, not just oaks.

Aphids in trees are a common problem; we've gotten a lot of calls and emails about them (and the stinging insects their honeydew attracts) this season. So at the first sign of any 'sooty' honeydew, spray the tree hard with sharp streams of water; a pressure washer would be ideal for this kind of work. Studies have found that being hit with sharp streams of plain water are a more effective aphid control than pesticides; the key is to make that stream a laser-like shot of H2O.

And if you want to go for the gold, make several timed releases of beneficial insects whose larval forms feed on aphids, like ladybugs, which are good, and lacewings, which are even better. They're available to homeowners via mail-order and just plain fun to have around. As am I.

Oh, and again, never feed trees chemical fertilizer or use chemical fertilizers near where the affected trees are growing. The lush, unnaturally fast growth these chemicals cause will attract every aphid in the area.

And if the {quote} 'sap' being clear means that it IS 'drippy nut disease'?

The potential cures here are going to be close to the same. Although the disease is caused by an unpronounceable bacterium, insects like filbert weevils and a caterpillar called the 'filbert worm' cause the actual damage to the acorns. And it's very common for oak tree aphids to also get in on the action. I would powerwash the aphids out of the tree at the first sign of sooty 'sap', and then begin spraying the original form of Bt—the organic caterpillar control—when the acorns reach a certain size. Your local county agricultural extension office should be able to tell you when the 'worms' are first becoming active.

(And, as we always note, Bt only harms caterpillars (often misnamed as 'worms') that chew on the sprayed leaves. It poses zero harms to bees, people, birds, frogs, toads, pets, etc.)

Now: What about the weevils we just mentioned? And why do all these nut-specific pests have the word 'filbert' in their name?

Based on regional preference, 'Filberts' are either a specific variety of hazelnut or another name for hazelnuts in general—and hazelnuts by any name are a cash crop that a lot of research has been devoted to. The same pests attack the acorns on oak trees, but there's no commercial value in acorns and so the research has all been devoted to the filberts, and the pests got their common name from that cash crop.

Oh—and before we finish up, we need to point out that the stinging culprits here are members of the wasp and hornet families. Native bees don't sting, and honeybees won't sting unless you step on them. If the attacker looked like a bee, it was almost certainly an aggressive yellowjacket.

--- Steve in Rockville Maryland

A.Wait a minute—haven't I answered this question already in a recent phone call on the show and in a previous Question of the Week? Its aphids up in the tree pooping out their sweet 'honeydew', which in turn attracts all kinds of insects, right?!

Yes and no. Steve might well have aphids in his tree; there's even an aphid species that's specific to oaks. But the wonderful euphemistic 'honeydew' that's pooped out by aphids is blackish in appearance, not the clear material Steve has described. (Aphid honeydew is so dirty looking that it's often described as 'sooty'.) As am I.

Steve's problem sounds more like (and I am not making this name up) 'drippy nut disease'. The unusually warm weather we've had in the mid-Atlantic region this season and the clear color of the fluid are strong clues to this diagnosis. The cause is a bacterium that infests nuts (in this case, acorns) that have been insect damaged, and it won't stop until the acorns drop. So for now, Steve needs to diligently clean the sticky stuff off the driveway and walkway with a pressure washer.

He should also put out lots of wasp and hornet traps to knock down the stinging insect population. And he should collect and destroy all the dropped acorns this fall.

And then there's the cars. He needs to get to a car wash ASAP and get every last bit of that 'sap' off the cars. Then he should try and park someplace else until the acorns fall, use car covers, or rinse the new 'sap' off every day. These drippings can be impossible to remove if left on for a long time.

Now—can this problem be prevented in future seasons?

An important component of trying to prevent future infestations is to avoid using chemical fertilizers on the lawn, or especially on the tree itself. High-powered chemical fertilizers make plants much more prone to insect attack. And whether this is drippy nut disease or oak leaf aphids, insects are at the heart of problem. Use corn gluten meal, compost or a bagged organic lawn fertilizer on the turf and don't worry about getting it too close to the tree; any 'leftovers' will give that oak a nice gentle feeding.

OK—now, let's talk to all trees, not just oaks.

Aphids in trees are a common problem; we've gotten a lot of calls and emails about them (and the stinging insects their honeydew attracts) this season. So at the first sign of any 'sooty' honeydew, spray the tree hard with sharp streams of water; a pressure washer would be ideal for this kind of work. Studies have found that being hit with sharp streams of plain water are a more effective aphid control than pesticides; the key is to make that stream a laser-like shot of H2O.

And if you want to go for the gold, make several timed releases of beneficial insects whose larval forms feed on aphids, like ladybugs, which are good, and lacewings, which are even better. They're available to homeowners via mail-order and just plain fun to have around. As am I.

Oh, and again, never feed trees chemical fertilizer or use chemical fertilizers near where the affected trees are growing. The lush, unnaturally fast growth these chemicals cause will attract every aphid in the area.

And if the {quote} 'sap' being clear means that it IS 'drippy nut disease'?

The potential cures here are going to be close to the same. Although the disease is caused by an unpronounceable bacterium, insects like filbert weevils and a caterpillar called the 'filbert worm' cause the actual damage to the acorns. And it's very common for oak tree aphids to also get in on the action. I would powerwash the aphids out of the tree at the first sign of sooty 'sap', and then begin spraying the original form of Bt—the organic caterpillar control—when the acorns reach a certain size. Your local county agricultural extension office should be able to tell you when the 'worms' are first becoming active.

(And, as we always note, Bt only harms caterpillars (often misnamed as 'worms') that chew on the sprayed leaves. It poses zero harms to bees, people, birds, frogs, toads, pets, etc.)

Now: What about the weevils we just mentioned? And why do all these nut-specific pests have the word 'filbert' in their name?

Based on regional preference, 'Filberts' are either a specific variety of hazelnut or another name for hazelnuts in general—and hazelnuts by any name are a cash crop that a lot of research has been devoted to. The same pests attack the acorns on oak trees, but there's no commercial value in acorns and so the research has all been devoted to the filberts, and the pests got their common name from that cash crop.

Oh—and before we finish up, we need to point out that the stinging culprits here are members of the wasp and hornet families. Native bees don't sting, and honeybees won't sting unless you step on them. If the attacker looked like a bee, it was almost certainly an aggressive yellowjacket.

-

Helpful Products from Gardens Alive!

-

Gardener's Gold™ Premium Compost

Gardener's Gold™ Premium Compost

Gardens Alive! & Supplies

Gardens Alive! & Supplies