New Thoughts on the Soil-Borne Wilts that Terrify Tomatoes

-

Helpful Products from Gardens Alive!

-

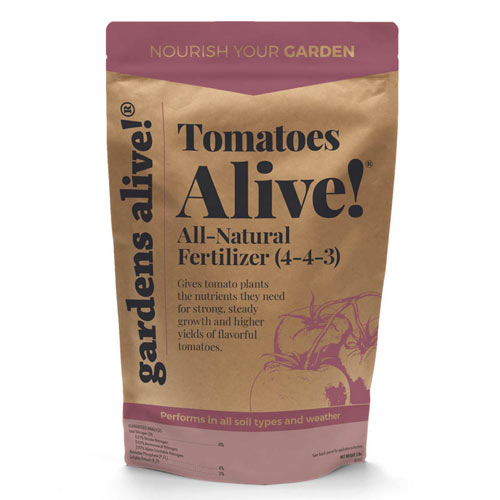

Tomatoes Alive!® Fertilizer

Tomatoes Alive!® Fertilizer

Q. Frank in Warrior's Mark PA (near Penn State) writes: "My wife and I enjoy fresh tomatoes, but our garden has limited space, and the general advice is not to grow tomatoes in the same location every year because of soil-borne wilts. Might adding beneficial bacteria be helpful?"

A. The answer to your actual question is 'no', no product--organic or natural--can do that. But there are some cultural conditions you can provide that may help a lot.

There are several pathogens that cause tomato plants to wilt. The biggest two are verticillium, which strikes mostly in cool wet soils (yet another reason not to rush the season by planting early) and fusarium, which prefers warmer and more humid conditions. However--and this is important--both diseases can strike singly or together in any region.

I wanted to freshen up my answer to this perennial question, so I delved into the most recent research--from the Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology in New Haven, North Carolina State Extension, Clemson University, and the University of California at Davis.

My biggest 'light bulb' moment came when I learned that it might be possible to grow tomatoes in the same space without rotating. Most of the newer information I encountered mostly talked about what to do after your plants become infected, which is to destroy those plants promptly, clean the surface of the bed, and then, yes, abandon that spot for tomatoes (and eggplant) for several years. But you might not need to rotate if the following symptoms don't show up.

Signs and symptoms:

From the researchers at New Haven: "Fusarium is a systemic vascular disease. The pathogen enters tomato plants through their roots and colonizes the plant's vascular tissues, which clogs the xylem (I hate when that happens!) and causes drooping of leaves. Leaves often turn yellow; the affected plants become stunted; and production is poor."

Infection is caused by wounds from cultivation (be careful weeding!) or non-beneficial nematodes feeding on roots, which mostly occurs in the South. The optimum conditions for disease development are sandy, acidic soil and high levels of nitrogen fertilizer. The pathogen can survive many years as dormant mycelium in plant debris and in the soil without a host plant.

Resistant varieties and Grafted rootstocks are the prime methods of prevention. Seeds and plants labeled with the letters V and F are resistant to both wilts. Grafted tomatoes (an excellent act of prevention) take the tomato you want to grow and then graft it onto the rootstock of a variety known to be extremely wilt-resistant. (A VERY effective approach as the pathogen directly attacks the root system.) Always keep the graft ABOVE the soil line.

"[If disease strikes], rotate tomato and other solanaceous crops out of that space for 4-5 years to reduce the inoculum level in the soil. Prevent movement of infested soil clinging to machinery, transplants, vehicles, tools, and stakes. As there is no cure for Fusarium wilt, remove and destroy diseased plants from the field or garden and do not compost them. Raise the soil pH to 6.5-7.0 if it's low; fertilizers containing calcium can reduce disease severity." (Hey--just like blossom end rot!)

Clemson on verticillium: "The first symptoms appear when fruits begin to mature. Lower leaves turn yellow, sometimes on one side of the plant or one side of a branch. This is followed by leaf and stem wilting. When an infected stem is split lengthwise you will see browning close to the skin. It is this clogging of the vascular tubes that produces the wilting and yellowing. Verticillium proceeds more slowly than fusarium and the symptoms are more uniform throughout the plant. Both fusarium and verticillium symptoms begin at the bottom of the plant."

From UC Davis: "Verticillium wilt is difficult to distinguish from Fusarium, and positive identification may require culturing the fungus in a laboratory. Verticillium wilt seldom kills tomato plants but reduces their vigor and yield.

Older leaves on tomato plants infected with Verticillium appear as yellow, V-shaped areas. The leaf progressively turns from yellow to brown and eventually dies. Older and lower leaves are the most affected. Sun-related fruit damage (sunscald) is increased because of the loss of foliage. (So don't prune your suckers!) Symptoms are most noticeable during later stages of plant development when fruits begin to size up.

Recommendations:

Incorporate crop rotations. "Rotating to non-host plants at 4-5 year intervals is advised for disease control. The wide host range of the Verticillium wilt pathogen may limit possible rotational crops, but grass and wheat species are recommended." (Grow cat grass there!)

Discard infected plant material. "The fungus can survive for extended periods of time within plant tissue. Immediate removal of infected plants is necessary to discourage the persistence of the pathogen."

Grow early-maturing varieties. "Quick-to-mature cultivars are likely to begin producing fruit before they completely succumb to disease. This can improve fruit yield in fields with a history of Verticillium wilt."

Control weeds. "Asymptomatic but infected weeds can spread the disease. Fields should be frequently and diligently maintained."

McGrath back with the summing up:

Plant your tomatoes in warm, well-drained soil; don't use fertilizers containing high amounts of nitrogen (the first number on the package's listed NPK ratio) but do add calcium.

Watch your plants carefully, but don't worry until one of these bad actors shows up for the first time.

A. The answer to your actual question is 'no', no product--organic or natural--can do that. But there are some cultural conditions you can provide that may help a lot.

There are several pathogens that cause tomato plants to wilt. The biggest two are verticillium, which strikes mostly in cool wet soils (yet another reason not to rush the season by planting early) and fusarium, which prefers warmer and more humid conditions. However--and this is important--both diseases can strike singly or together in any region.

I wanted to freshen up my answer to this perennial question, so I delved into the most recent research--from the Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology in New Haven, North Carolina State Extension, Clemson University, and the University of California at Davis.

My biggest 'light bulb' moment came when I learned that it might be possible to grow tomatoes in the same space without rotating. Most of the newer information I encountered mostly talked about what to do after your plants become infected, which is to destroy those plants promptly, clean the surface of the bed, and then, yes, abandon that spot for tomatoes (and eggplant) for several years. But you might not need to rotate if the following symptoms don't show up.

Signs and symptoms:

From the researchers at New Haven: "Fusarium is a systemic vascular disease. The pathogen enters tomato plants through their roots and colonizes the plant's vascular tissues, which clogs the xylem (I hate when that happens!) and causes drooping of leaves. Leaves often turn yellow; the affected plants become stunted; and production is poor."

Infection is caused by wounds from cultivation (be careful weeding!) or non-beneficial nematodes feeding on roots, which mostly occurs in the South. The optimum conditions for disease development are sandy, acidic soil and high levels of nitrogen fertilizer. The pathogen can survive many years as dormant mycelium in plant debris and in the soil without a host plant.

Resistant varieties and Grafted rootstocks are the prime methods of prevention. Seeds and plants labeled with the letters V and F are resistant to both wilts. Grafted tomatoes (an excellent act of prevention) take the tomato you want to grow and then graft it onto the rootstock of a variety known to be extremely wilt-resistant. (A VERY effective approach as the pathogen directly attacks the root system.) Always keep the graft ABOVE the soil line.

"[If disease strikes], rotate tomato and other solanaceous crops out of that space for 4-5 years to reduce the inoculum level in the soil. Prevent movement of infested soil clinging to machinery, transplants, vehicles, tools, and stakes. As there is no cure for Fusarium wilt, remove and destroy diseased plants from the field or garden and do not compost them. Raise the soil pH to 6.5-7.0 if it's low; fertilizers containing calcium can reduce disease severity." (Hey--just like blossom end rot!)

Clemson on verticillium: "The first symptoms appear when fruits begin to mature. Lower leaves turn yellow, sometimes on one side of the plant or one side of a branch. This is followed by leaf and stem wilting. When an infected stem is split lengthwise you will see browning close to the skin. It is this clogging of the vascular tubes that produces the wilting and yellowing. Verticillium proceeds more slowly than fusarium and the symptoms are more uniform throughout the plant. Both fusarium and verticillium symptoms begin at the bottom of the plant."

From UC Davis: "Verticillium wilt is difficult to distinguish from Fusarium, and positive identification may require culturing the fungus in a laboratory. Verticillium wilt seldom kills tomato plants but reduces their vigor and yield.

Older leaves on tomato plants infected with Verticillium appear as yellow, V-shaped areas. The leaf progressively turns from yellow to brown and eventually dies. Older and lower leaves are the most affected. Sun-related fruit damage (sunscald) is increased because of the loss of foliage. (So don't prune your suckers!) Symptoms are most noticeable during later stages of plant development when fruits begin to size up.

Recommendations:

Incorporate crop rotations. "Rotating to non-host plants at 4-5 year intervals is advised for disease control. The wide host range of the Verticillium wilt pathogen may limit possible rotational crops, but grass and wheat species are recommended." (Grow cat grass there!)

Discard infected plant material. "The fungus can survive for extended periods of time within plant tissue. Immediate removal of infected plants is necessary to discourage the persistence of the pathogen."

Grow early-maturing varieties. "Quick-to-mature cultivars are likely to begin producing fruit before they completely succumb to disease. This can improve fruit yield in fields with a history of Verticillium wilt."

Control weeds. "Asymptomatic but infected weeds can spread the disease. Fields should be frequently and diligently maintained."

McGrath back with the summing up:

Plant your tomatoes in warm, well-drained soil; don't use fertilizers containing high amounts of nitrogen (the first number on the package's listed NPK ratio) but do add calcium.

Watch your plants carefully, but don't worry until one of these bad actors shows up for the first time.

-

Helpful Products from Gardens Alive!

-

Tomatoes Alive!® Fertilizer

Tomatoes Alive!® Fertilizer

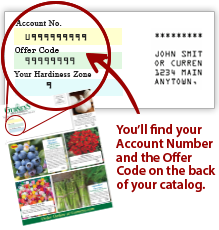

Gardens Alive! & Supplies

Gardens Alive! & Supplies